Understanding Your Character

By Lindsay Alcock

Understanding your own character has huge significance with how you treat others, whether it is your teammates, business associates, family members or friends. Most importantly, by predicting your own behaviour in a given situation, you will be able to lower your stress levels and through enhanced communication, prevent unnecessary conflict with others. In Olympic training and competition, it is necessary to employ strategies for improving mental performance because it has a powerful influence on the outcome. The same strategies can also be employed in the business workplace as it is still a team dynamic in the pursuit of success. Professional sport organizations and businesses will benefit from knowing the character-type of an individual applying for a job or hoping to make a sports team. Through the application of Psychocybernetics and a systematic approach to understanding our own innate character, it is possible to achieve optimum performance.

Late in 2002, I was introduced to the field of Psychocybernetics and its champion, Dr. Peter Guy. He is a sport theoretician and psychocyberneticist who specializes in the development of human performance in both sport and business. Psychocybernetics is the complex science of the human system and how we interact with other systems we encounter in daily life. I am a member of the Canadian Skeleton team and I proudly represented Canada at the 2002 Olympic Winter Games in Salt Lake City, Utah. Our sport is considered by many as extreme. Well, who is kidding who? It is downright ludicrous to some. We travel headfirst down an ice track with our chin literally inches off of the ice. The speeds we reach can range from anywhere between 115 km/h to 130km/h. Dr. Guy has developed a performance blueprint for me over the next three seasons of competition, leading ultimately to superior performance at the next Olympic Winter Games in Torino, Italy in 2006.

The concept of Psychocybernetics was fascinating to me because it provided an answer to what I had already been feeling back in 1998 when I entered the competitive world of Skeleton at age 21. It was when the stakes became higher at competitions that I came to realize how important it was to have an understanding of my own character to optimize performance. Simply stated, character refers to our own innate, personal make-up – one that changes naturally as one ages. Each character comes with its own dynamism and this is extremely important because your dynamism determines your energy levels. For example, an individual with an exodynamic system creates much more energy than is required for the physiological functioning of the body and so this person must find methods to expend this excess energy. Some athletes expend this energy through vigorous warm-up routines, complete with grunting, punching walls, and non-stop pacing in the starthouse.

An athlete’s dynamism must fall no further along than statism because of the required energy reserves needed to carry out their chosen sport. A person with a static dynamism creates an equal amount of energy with the amount of energy that is channelled. From my own assessment by Dr. Guy, I was found to be a static character. I only have an available store of energy for performing and beyond that I can become completely drained.

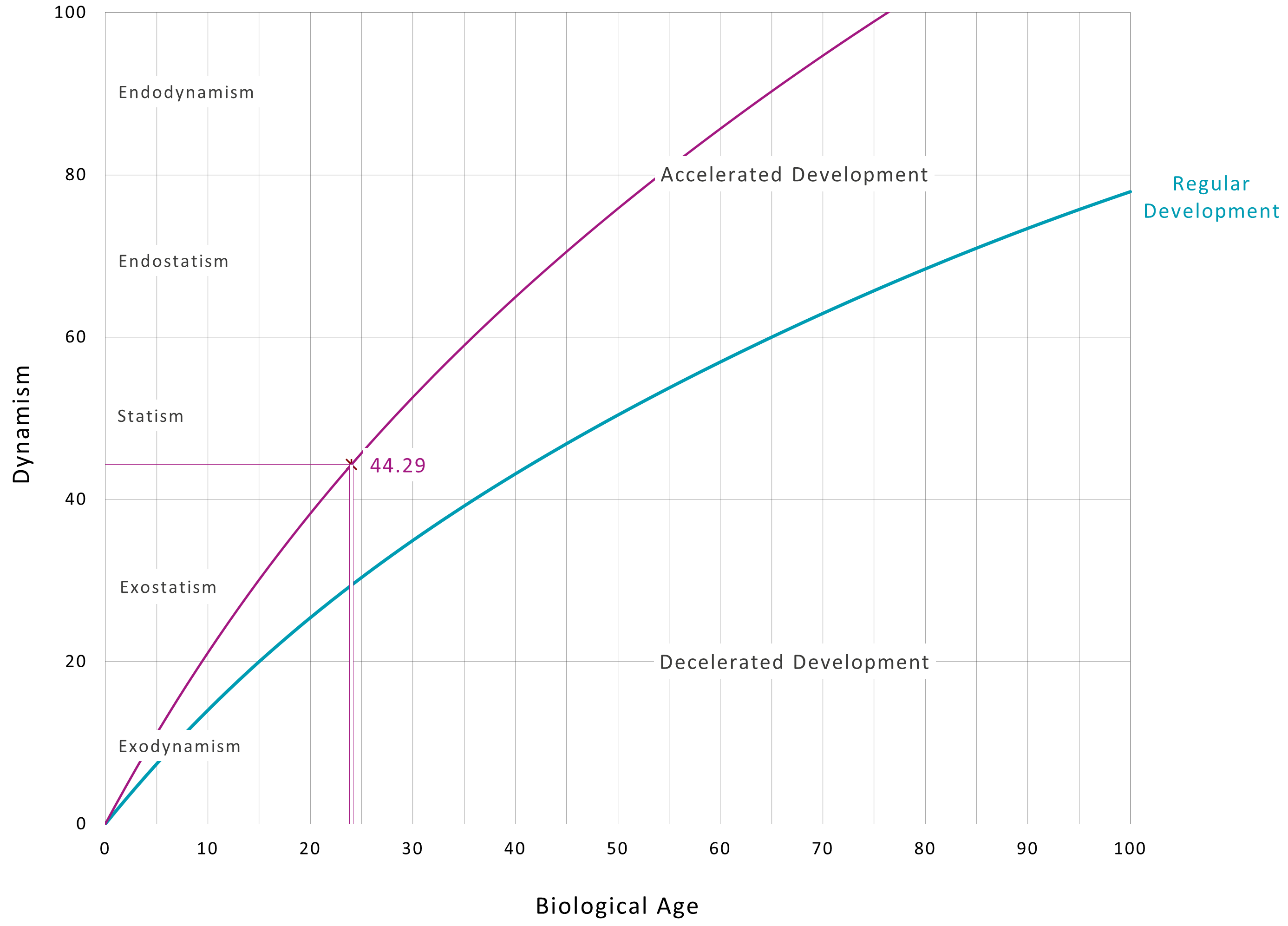

According to my dynamism development curve as shown in Fig. 1. below, I will be making a transition into the next dynamism, known as endostatism, when I reach the age of 37. I will have even less energy available then, to the point that I will have an energy deficit. This time in my life will coincide with retirement from elite sport because physically I will not have the energy to maintain peak performance levels. There are strategies, however, to gain the energy back through increased levels of power and delegating tasks. A career in coaching, for example, would allow me to address the decreased energy levels available within this particular dynamism, while still improving my levels of leadership and management.

Fig. 1.

The application of individual development curves from a “Psychocybernetics Character Assessment” can play an integral part in draft selection procedures for sports teams. For example, in the world of professional hockey, it would be extremely advantageous and cost-effective to perform character assessments on potential draft picks so that team management can better predict the future potential for these rising stars. By understanding the character development profile of these athletes, decision makers have a more objective tool to better understand a young athlete’s potential for future success in the NHL.

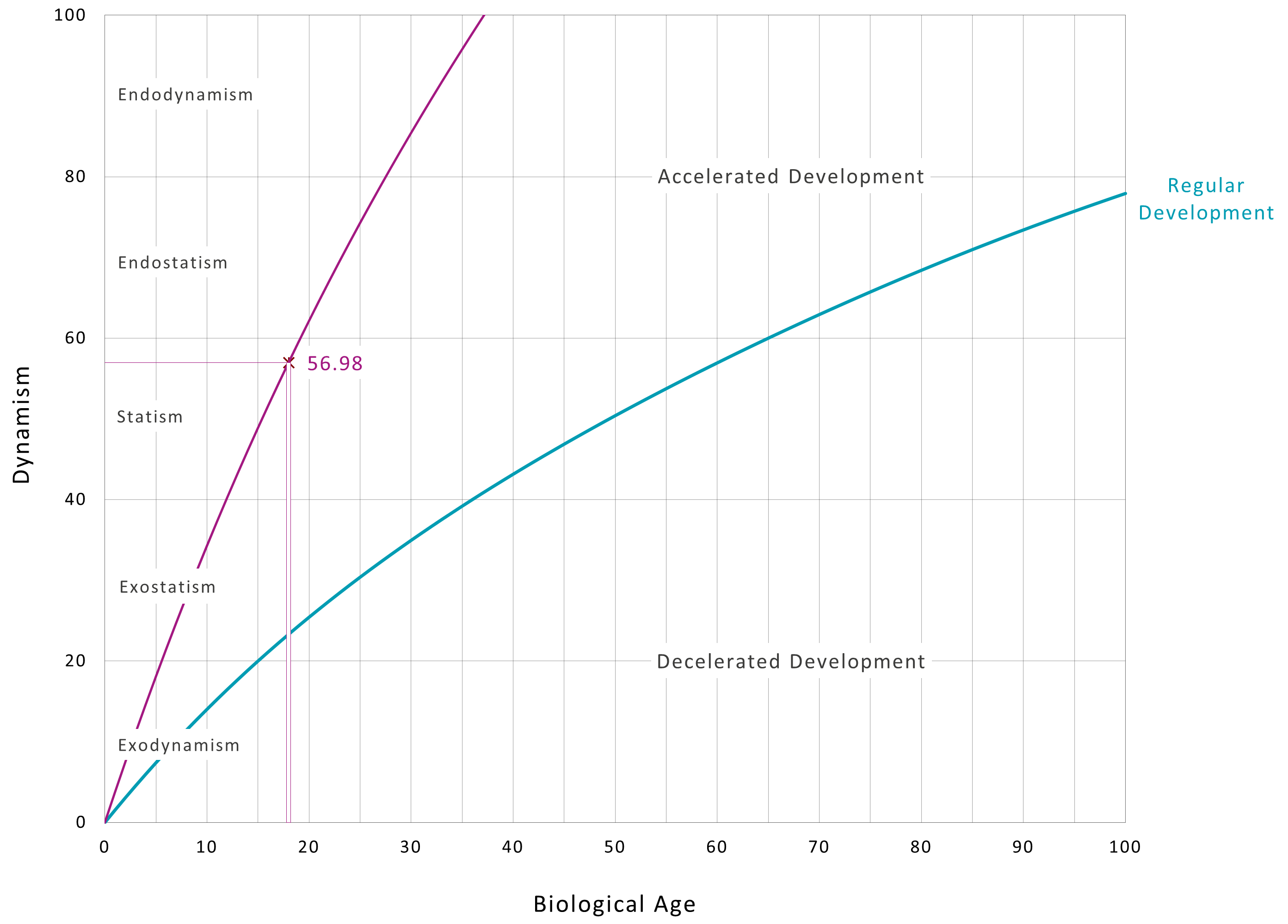

For example, the development curve shown in Fig. 2. displays data from a young hockey player with a static character before the age of 20. It reveals that this potential draft pick has already reached his performance peak in hockey and will not make a good long-term contribution to the hockey club because of his accelerated development curve. Although he may show superior skills in his late teens, he will soon enter the endostatic dynamism in his mid-twenties. At this point the draft candidate will experience an energy deficit related to endodynamism. This energy deficit will compromise the ability of this draft choice to perform at the level necessary for an NHL caliber player.

Fig. 2.

As a beginner Skeleton slider in 1998, I was just reaching the transition point between exostatism and statism. I had begun to recognize sources of stress that had detrimental effects on my performance and that ultimately drained my valuable energy supply. Through trial and error, I was able to determine what variables motivated me to bring performance to another level. By the end of my first season, I had developed a unique tradition of writing in my journal and summarizing the emotional highlights of the season. I observed that my highlights had very little to do with my actual Skeleton performances and everything to do with my relationship with those around me. In reviewing my diary I noticed that I was analyzing my teammates’ characters and how each individual interacted with another. I observed that I shared more compatibility with some people and was clashing with other.

My static dynamism and increased awareness of its qualities allowed me to adjust my own personal environment, especially while on Skeleton tour, so that I could avoid conflict with another person(s) of incompatible character. In turn, I lowered my stress levels and perhaps that of the rest of the team because the potential conflict was successfully curtailed. This task is rarely easy and I tend to rely on past behaviours or patterns exhibited by these individuals to predict their behaviours in future situations. It becomes a delicate skill that requires a keen sense of surroundings, key events, and timing. For example, did the behaviour occur in a high-stress race setting or at a low key, post-race dinner? Does this person only act out when there is an audience or do they tend to vent mostly when it is just the two of us together?

Over time, I became adept at recognizing teammates who would start showing signs of stress and decreased tolerance. I sensed that conflict was all too near and in order to preserve my own energy levels, I took steps to remove myself from the situation or performed a task that would inevitably lower stress levels for everyone. Travel can be a huge stressor for some individuals so you could expect that if there were any delays in flights or other modes of transport, conflict could manifest itself due to low tolerance levels being exhibited. Only minutes before the start of a major race, an exostatic teammate would exhibit nervous energy and their way for expending it would be talking to all those who were willing to listen. For a static such as myself, I tend to conserve the energy I do have and will generally keep quiet on these occasions. If it means ignoring the exostatic beside me, than so be it!

I had to do my own investigative work and that meant recording any significant behaviours, conversations or past occurrences into a diary. I often speculated what may have brought their behaviour on or what physical or psychological stressors may have contributed to the outburst. We are all at some point going to reach our breaking threshold but having an awareness of the trigger is crucial. Through quantitative data from the character assessment, Dr. Guy revealed that I have high tolerance levels but if pushed beyond my threshold, I can react spontaneously with verbal venting, or simply run away from the stressor altogether. In addition, I have low persuadability – once I have an idea in my mind, it will take a fair amount of convincing and sufficient evidence to sway my opinion. This stubbornness I exhibit can be potentially negative but the fact that I am aware of it and can recognize environments that exacerbate it means I have more control over it.

By age 23, I had two straight years of unsuccessful attempts at making the National Skeleton Team. My performance had plateaued and it seemed that the harder I tried, the worse the results became. What I didn’t understand at the time (before being introduced to Psychocybernetics) was that I was entering into a difficult transition between exostatism and statism. Transition periods are almost always filled with internal conflict as the individual is still dabbling in the old dynamism but struggling to break into the next realm. A good analogy is ordering a meal at a restaurant. During my transition period, I could find two choices on the menu but would have difficulty narrowing it down to the one I wanted. The exostatic side of me would want to go wild and crazy with the spicy jambalaya but the static side would lean more towards the chicken salad because it is healthier and less stressful on the taste buds!

On a more serious note, I was experiencing conflict in other areas of my life too including conflict in my family, uncertainty about further education, and my own personal struggles with identity. My exostatic side wanted to continue living the high life which meant staying in Mom and Dad’s condo (rent free), with the added guilt of my brothers struggling to make ends meet with their day jobs. I was out traveling the world and having fun with my friends with no real commitment to anything but sport. This went against everything that a static would want: stability, direction, purpose, and financial security.

I was nearing the end of my University education and the “what next?” dilemma was creeping into my daily thoughts. My priorities were shifting towards a more responsible attitude that included a longing to be self-sufficient in areas of finance, employment, and housing. I was being pulled in the direction of what society intended for me and that meant shifting my efforts towards a “real” job. I was starting to get tired of telling people what I did for a living (“ I am a full-time amateur athlete”) and getting a response back like, “…uh huh…so what else do you do?”. I was starting to realize that I needed to choose between the real world and pursuing Skeleton. The stressed areas in my life were all contributing to my somewhat stale performance in Skeleton. The transition I was experiencing was leading me astray and preventing a definitive path to be carved out.

Once I achieved balance again in areas of family, partly due to the reassurance from my parents that they were committed to supporting my sport career, and in fully accepting my talents as an athlete, I was ready to put my full effort back into Skeleton competition. Eventually, the transition from exostatism to statism became more complete and much of my prior internal conflict abated. Team selections came around again in October 2001 and it was then that I finally made the breakthrough I was looking for. I became a member of the National Skeleton Team by finishing 1st overall in the team races. Only a couple of months later, I won my first ever Gold medal at a World Cup competition hosted in Calgary, Alberta. It was the start to a Cinderella-like story as I ventured towards securing a berth to the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics.

Many of my early diary entries made reference to the tangible things in sport – getting to wear the team Canada jacket, negotiating sponsorship deals, giving television interviews, and acquiring prize money and fame. I focused my efforts on defeating individual people and forgot the fact that Skeleton was a race against the clock. Ideally, there should be no personal grudge onto others should you not pass the finish line first. But our sport never works that way. What happens on the ice is most certainly reflected off the ice and oftentimes, this is when the conflicts can arise within relationships.

Over the last five years of competitive sliding, I have managed to employ certain strategies for reducing my stress levels so that I can perform successfully under extreme pressure. I effectively adjust my own environment, given my understanding of statism. It is an amazingly empowering experience to know that I can have an influence on my emotional state and ultimately, my athletic performances. I love to be a tourist when I am at competitions around the world so occasionally I throw on my winter jacket and toque and embark on a walking adventure through the small side streets of the local villages. The rejuvenation of my spirit comes from inhaling the crisp, winter air into my lungs and feeling my cheeks burn. These solitary walks clear my head, refuel my energy reserves and provide much needed respite away from our familiar hotel walls. Oftentimes, these walks happen when conflicts arise within the team and when I feel pulled down by the emotional weight of it all. There is nothing more delightful than exploring little corners of the village or treating myself with a piping hot chocolate in a quaint, dimly lit pub. On occasions like these, I pack my journal around with me so that I can vent my emotions on paper in a healthy, non-confrontational way. It is a wonderful keepsake that records my surroundings and the people I meet along the way.

It is important for me to keep close tabs, by phone or email, with my partner and family while on tour. I crave their positive energy and as Dr. Guy’s assessment indicated, home and family is a main area of concern for me. I place tremendous value on lasting, long term relationships and the devotion for my loved ones is an essential component to my static character. Friends also play a strong role in my de-stressing strategies and what is sure to bring light into my eyes is a good game of pinball. Currently, I still hold the title of grand master champion on the Pinbot machine at the Hampton Inn in Park City, Utah. I love to play cribbage, rummy, and a whole host of other card games, as long as the people I play with exude positive vibes and make me laugh!

There was no better way to show this strategy at work than at the 2002 Salt Lake Olympics, on the morning of my Skeleton event. While my competitors were fending off nausea and pre-race angst, I was relaxing in my own little corner, reading Lord of the Rings, only 1 ½ hours away from the first Women’s Olympic heat. At one point, I even stepped outside onto the balcony overlooking the race track to breathe in the icy, winter air and took on the role of spectator instead of athlete. I remember asking myself, “They are coming to watch us slide??” It was an amazing moment to have because I hear so often about the typical first-timer Olympian and how they absolutely lose themselves in the chaos. Some never fully absorb the moment unfolding before them and it would be a shame if they never had a chance to re-live it again at another Olympics.

At the race line for the first heat, I calmly smiled inside my helmet at the start line. It was a victory to even be standing there! I pushed off the line with as much vigor and power as possible and slid down the windy 15 corner track aware of only two things… the myriad of colours from the spectators whooshing past me in my periphery and the familiar sound of the wind hitting my speed suit. To this day, I truly feel that I raced the best I could at the 2002 Olympics and will always cherish the emotions felt and shared with my family throughout the entire process of qualifying and competing.

The start to the 2002/2003 season was as successful as I could have imagined. The first race in November following the Olympics was a clearcut victory on my home track in Calgary, Alberta. I achieved a track and push record and finished on the top of the podium with over a second of combined time between my closest competitor. I had set the bar high at the start and was ready to maintain this dominance at the World Cup in Salt Lake City and following that in Lake Placid, New York. Going into the third race in Lake Placid, Dr. Guy realized that as a static, I needed to start coming down from my “glory” of taking Gold in Calgary and a Silver medal in Salt Lake City.

In sport, and in the business world, we have to allow for these peaks and valleys to occur because many of us are not physically and/or psychologically capable of staying at the top all the time. Dr. Guy’s suggestion to lighten the intensity was a welcome one because it seemed that my successes had spawned some animosity within my own team. The negativity that came from this created an undesirable atmosphere that was draining to my energy levels. I needed an action plan to face this unexpected hurdle and so I treated Lake Placid as part of my Christmas break.

From my journal entries that week, I was surprised by how the strategy unfolded to result in the most unexpected outcome of my career:

December 7, 2002.

During training this week, I kept referring back to Dr. Guy’s words about taking it easy and treating this week as part of my training and of course, part of my Christmas holidays. I found myself smiling a lot more at the track. From past experience, this track often left me mystified and completely frustrated because I couldn’t figure it out. Instead, I went into every run with one or two small goals in mind. I tried to find things or specific feelings with the track that were FUN and in the process, I learned something more about a particular corner that I kept note of. Even if I messed up on a corner, I was able to chuckle to myself about it while in track.

This week of training at Lake Placid was actually a refuelling process that I needed psychologically. After all of the hype surrounding my last two races, my body was craving downtime and Lake Placid was the place to do it. Throughout training, I was consistently finishing 15th and 16th which created excited rumblings amongst the women in the field. Many competitors started factoring me out of the race and that was probably the best outcome I could have expected. Suddenly, the pressure started to come off me and I was able to execute the plan even more effectively. On race day, I clearly remember going into corner #1 thinking, “this is an absolute BLAST!” I was absolutely relaxed and had no expectations or preconceived notions throughout the World Cup race. When I saw the clock at the bottom showing first place, I actually giggled to myself and immediately pictured Dr. Guy laughing to himself too at the top of the track. He knew the plan would work, despite my initial qualms with “taking it easy” during training. My competitive spirit drives me to be my best at all times but when asked to ease off the intensity a little, I am perplexed about how to go about doing that. That whole week, I kept asking Dr. Guy for clarification- “You actually want me to slow down my sprint start??!!”. This was the most bizarre but treasured World Cup win I have ever experienced.

What I was learning throughout that week in Lake Placid was the art of choosing when to peak my performance and when to downshift gears to ease the psychological burden that can mount in elite performance. It was a completely empowering experience knowing that I could control the outcome to some degree. These peaking performance strategies will be absolutely essential to master as I make my journey towards superior performance at the 2006 Olympic Winter Games in Torino, Italy.

Peak performance can be reached only by fully understanding your own innate character. The application of Psychocybernetics in sport and business can lead to improved communication and decreased stress levels for all groups involved. The human system is extremely complex but by using strategies that are unique to our own character, we enable ourselves to create the environment we require to succeed. In Skeleton, I can try to accurately predict or anticipate when conflicts may arise by knowing the characters and dynamism of my teammates. When equipped with the knowledge of my own strengths and weaknesses, I can implement appropriate strategies and techniques to optimize personal performance in all areas of my life – sport, self, and family. Employers and sport organizations can be more confident about the potential contributions that an individual can offer to them based on data-based development curves for that person. On a personal level, we can accept and embrace who we are as individuals and gain strength in knowing that we have the power to tailor our lives to achieve our goals and dreams.